Registers accessed from Lahore Museum digitised, records of WW-1 soldiers from undivided Punjab now a click away

On the 103rd anniversary of the capstone of World War I (July 28, 1914-November 11, 1918), to be observed as Remembrance Day on Thursday across the globe, descendants of the British Indian Army dogfaces from concentrated Punjab can eventually hope to have some of their questions answered – after a delay of over a century.

Seven times after London- grounded UK Punjab Heritage Association (UKPHA) began penetrating and digitising the‘Punjab Registers’– documents detailing the account of each dogface who shared in WW-I from concentrated Punjab – from the Lahore Museum in Pakistan, the organisation, in association with the University of Greenwich, will launch the digital platform http//www.punjabww1.com, where one can find and track each detail of the dogface by entering the name of the vill or quarter on the chart of concentrated Punjab.

The first ever similar digitization design, with information sourced from‘Punjab Registers’and also transcribed, digitized and counterplotted can help families, cousins and extended connections of the dogfaces eventually get a check as till now utmost of them were living with just bits and pieces similar as a order, a document, a brand or other war cairn — knowing that their ancestor was in WW-I but ignorant of how they failed, if they were missing, or failed after the war.

Phase-1 of the platform will be launched with details of three sections – Ludhiana, Jalandhar ( also Jullundur) and Sialkot ( now in Pakistan) – on Thursday, where druggies can find details of WWI dogfaces.

For case, if one enters‘Ghalib Kalan, Ludhiana’as the vill name, it shows details of 173 dogfaces, including the‘ original Register Page’where that names are mentioned in records.

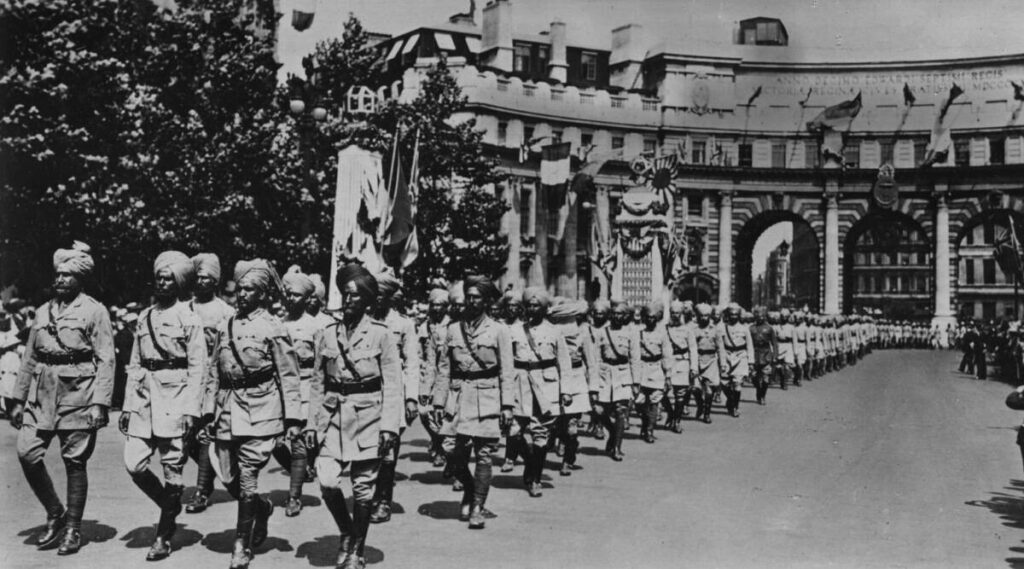

UKPHA author Amandeep Singh Madra told The Indian Express that this begins to tell the story of 5 lakh men from Punjab who went to war – 5 per cent of the total British force. “ It’s a noway ahead seen library that shows the names and townlets of every man from Punjab who served in WW-I. It lets families trace their details just by entering the name of the dogface and the vill or either of them,” he said.

“ Although account for lower than 8 per cent of the population of British India at the time, Punjabis of all faiths – Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs – made up around a third of the Indian Army. In 1919, after the war had concluded the Punjab government collected a series of registers listing the names of every man that had served in the Army – the records have remainedun-researched for nearly a century.

Comprising some runners, listing further than individual names, the‘Punjab Registers’ give vill-by- vill data on the war service and pensions of Punjabi recruits, as well as information on their family background, rank and troop. They offer a detailed breakdown of the recruiting practices of the Indian Army a century agone and into the individual dogfaces revealing perceptivity into their occupational, social, political and faith backgrounds. In some cases they also detail the awards they entered and the far flung theatres of war that they served in, and from which at least didn’t return. They also help us to understand why Punjab was so poorly affected by the influenza epidemic which raged across the globe from 1918 and which was largely brought back by returning dogfaces,” Madra said.